Reflections of a Social Ecologist (Part 2)

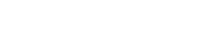

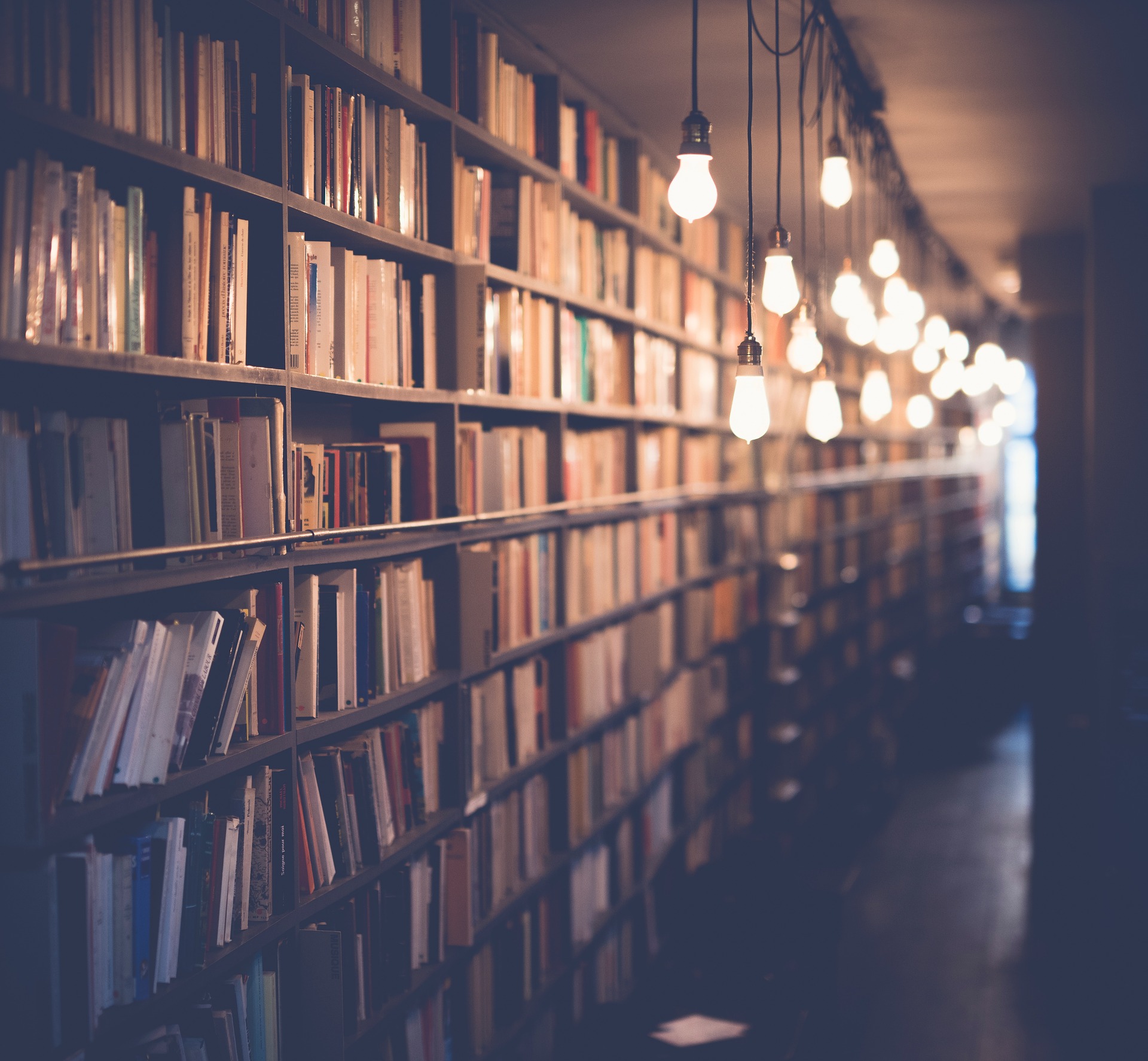

Peter F. Drucker

“Born to See, Meant to Look”

The Work of the Social Ecologist

If social ecology is a discipline, it not only has its own subject matter. It also has its own work—at least for me. But it is easier to say what the work is not than to be specific about what it consists of.

I am often called a “futurist.” But if there is one thing I am not—one thing a social ecologist must not be—it is a “futurist.” In the first place it is futile to try to foresee the future. This is not given to mortal man. And the idea that ignorance and uncertainty become vision by being put into a computer is not a particularly intelligent one. One problem is that the things the most brilliant and most successful predictor never predicts are always the things that are more important than the things he does predict. Futurists, always measure their batting average by how many of things they have predicted came true. They never count how many of the important things that came true they did not predict.

A good example is the most successful futurist in recorded history, the French science fiction writer Jules Verne (1828-1905). Most of the technologies he predicted have come true. But he—probably quite unconsciously—assumed that society and economy would remain what they were around 1870—and the changes in society and economy have, of course, been at least as important as the new inventions.

But also, and more important,

the work of the social ecologist is to identify the changes that have already happened. The important Challenge in society, economy, politics is to exploit the changes that have already occurred and to use them as opportunities.

The important thing is to identify the “Future That Has Already Happened”—the tentative title of another book which I did not write, a book which was intended to develop the methodology for perceiving and analyzing these changes which had happened—and irreversibly so—but which had not yet had a impact, and were indeed not yet generally seen.

One example is my identifying around 1960 the social and industrial turnaround which had already occurred in Japan and which, within another ten years, propelled Japan into the first rank of economic powers. It was not hard to do so; one only had to look. But nobody else looked at that time.

While I did not write the “The Future That Has Already Happened,” I incorporated a good deal of the material into my 1986 book Innovation and Entrepreneurship

which shows how one systematically looks to the changes in society, in demographics, in meaning, in science and technology, as opportunities to make the future.

While I am wrongly acclaimed as a “futurist,” I am equally wrongly criticized for not being a quantifier. Actually I am an old quantifier. In 1929, not yet twenty, I published one of the first econometric studies. Like so much of this work it proceeded from a self-evident assumption by means of impeccable mathematics to an asinine conclusion to whit that the New York Stock Market could go only one way, that is up. The way such things go, this paper appeared in a highly prestigious economic journal in August or September of 1929, just a few weeks before the event which I had just proven to be “impossible,” actually occurred—that is a few weeks before the October 1929 Stock Exchange Crash (fortunately, there is no copy of the journal left, at least not in my possession). It was the last prediction, by the way, I allowed myself to indulge in. But I also taught statistics at one time, and helped organize the first operations research departments in American industry (in GE and the Bell Telephone System), and thus can hardly be accused of being unfamiliar with quantitative methods.

But quantification is scaffolding rather than the building itself. And one removes the scaffolding when the building is finished. More important, quantification for most of the phenomena in a social ecology is misleading or at best useless. The data are much too poor—as the great mathematician and methodologist of quantification, Oskar von Morgenstern (1902-1977) showed in his 1950 book On the Accuracy of Economic Observation. Moreover, most of the socioeconomic figures we use in the United States (gross national product for instance, balance of payments, occupational classifications in the census, and many more) are based on aggregates developed in the 1920s, and especially in the U.S. Department of Commerce while Herbert Hoover was its secretary from 1924-1928. And it is a rule in social and economic statistics that aggregates if more than thirty or forty years old are highly suspect; they must be assumed to be outdated.

But the most important reason why I am not a quantifier is that

in social and affairs, the event that matters cannot be quantified. It is the unique event that changes the statistical “universe” and with it what is “normal distribution.”

One example is Henry Ford’s ignorance in 1900 or 1903 of the prevailing economic wisdom according to which the way to maximize profit is to be a monopolist, that is to keep production low and prices high. Instead of which he assumed—foolishly according to his partners and to the other people who had invested in his business—that the way to make money was to keep prices low and production high. This, the invention of “mass production,” totally changed industrial economics—though a good many economists still have not heard of it. It would have been impossible, however, to quantify the impact even as late as 1918 or 1920, that is a full ten years after Ford’s success had made him the richest industrialist in the United States (and probably in the world), had revolutionized industrial production, the automobile industry and the economy altogether, and had, above all, totally changed our perception of industry.

The unique event that changes the universe is an event “at the margin.” By the time it becomes statistically significant, it is no longer “future” it is indeed no longer even “present.” It is already “past.”

To quantify social events that make a difference we would need a mathematics that was first called for by the seventeenth-century philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Leibnitz—the co-inventer of the calculus. He spoke of a “calculus of relevance,” that is of a calculus of qualitative change. But nobody even responded to the challenge for 250 years until John Maynard Keynes in his first major work. A Treatise on Probability (1911) tried to develop the statistics of the unique event—totally without success as he himself later admitted. New mathematical theories now promise to define the probability of the unique event. But so far there is not even the slightest sign of a quantitative method to identify and to define the unique event, that is of a quantitative method to show changes in meaning.

And until such a quantitative method is developed—if it ever will—

the social ecologist has to use qualitative means to find and assess qualitative change. This, however, is not “guesswork.” It is not “hunch.” It has to be a rigorous method of looking, of identifying, of testing

—what such a method has to be I tried to develop, at least in rough outline, in my 1986 book Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

Now as to what the work of the social ecologist is or should be, at least for me.

First of all, it means looking at society and community with the question:

What changes have already happened that do not fit “what everybody knows;” what are the “paradigm changes,” to use the now popular term? The next question: Is there any evidence that this is a change and not a fad? The best test: Are there results of this change? Does it make a difference, in other words? And, finally, one then asks: If this change is relevant and meaningful, what opportunities does it offer?

A simple example would be the emergence of knowledge as a key resource. For me, the decisive change, the event that alerted me that something was happening, was the GI Bill of Rights in the United States after World War II. This bill gave every returning veteran the right to attend college with the government paying the bill. It was a totally unprecedented development. In retrospect it is easy to see that it was the GI Bills of Rights that ushered in the knowledge society. But nobody saw it in this light in 1947 or 1948. I, however, asked myself a simple question: “If there had been such a Bill of Rights after World War I, would it have had an impact? Would many people have taken advantage of it?” It did not of course occur to anybody in 1918—less than thirty years before the post-World War II bill—to offer such a veteran’s benefit, though 1918 America was as generous to its veterans as 1946 America, if not more so.

But if such a bill had been offered in 1919 and had passed the Congress—a most unlikely assumption—practically nobody would have taken advantage of it. Then going to college was not seen as a meaningful opportunity for anyone but the children of the wealthy who did not need a GI Bill of Rights, or for a few who were so talented that their poverty did not matter. Universal high school education became meaningful after World War I; universal college education would have been meaningless then.

This then led to the question,

“What impact does this have on expectations, on values, on social structure, on employment, and so on?”

And once this question was asked—and I first asked it in the late 1940s—it became at once clear that knowledge had attained a position in society and as a productive resource which it had never had before in human history. It became very clear that we were on the threshold of a major change.

Ten years later, that is by the mid-fifties, this had become so clear that one could with confidence talk of a “knowledge society,” of “knowledge work” as the new center of the economy, and of the “knowledge worker” as the new work force and the one in the ascendant.

The next thing to say about the work of social ecologist is that

he must aim at impact. His goal is not knowledge; it is right action. In that sense social ecology is a practice—as is medicine, or law, or for that matter the ecology of the physical universe. Its aim is to maintain the balance between continuity and conservation on the one hand, and change and innovation on the other. Its aim is to create a society in dynamic disequilibrium. Only such a society has stability and indeed has cohesion.

This implies, however, that the social ecologist has a responsibility to make his work easily accessible. It rules out being “erudite.” In fact, in social ecology being “erudite” is incompatible with, and the foe of, being “learned.” The conceit that science is not “science,” is in fact not “respectable” unless it is unaccessible, is obscurantism. Before World War II the first-rate scholars in America, and especially scholars in the social and political sciences, wrote for the educated layman—as did the first rate historians of that day, as did Reinhold and Richard Niebuhr both, Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict, and even the economists of that day, and the psychologists. Max Weber wrote simply, clearly, and accessibly and published in magazines for the laity and even in the daily press—and so did Thorstein Veblen.

In 1927 a French philosopher, Julien Benda (1867-1956), published La Trahison de Clerks (The Treason of the Intellectuals), a blistering attack on the intellectuals of his day who for fashion’s sake betrayed their duty and embraced racism and demagoguery, whether Nazism or Communism. The following decades then amply proved Benda’s criticism—by the willingness of intellectuals all over Europe—and not just in Germany—to support Hitler, and equally by their willingness to support if not to idolize, Stalin.

I consider the obscurantism of today’s intellectuals equally to be betrayal and treason. In large part they bear the blame for the debasement of culture, especially in the United States. The intellectuals themselves plead that the laity has lost receptivity to knowledge, to science, to discourse and to reason. But this is simply not true. Whenever a scholar deigns to write decent prose he or she immediately finds a wide audience. I myself am an example. But so was Barbara Tuchman, among historians, Rachel Carson or Loren Eisele among ecologists of the physical universe, Irving Louis Horowitz among sociologists, and a good many others. The receptivity is there, and so is the need. What today passes for scholarship is nothing but arrogance.

This arrogance is least justifiable for a social ecologist. His job is not to create knowledge. It is to create vision.

He has to be an educator.

Finally, the work of the social ecologist requires, I am convinced, respect for language.

I would have respected language regardless of my field. The Vienna in which I was born in 1909 was extremely language-conscious. With his 1899 book Zur Kritik der Sprache (The Critique of Language), an Austrian, Fritz Mautner (1849-1923), founded what we now call the philosophy of language. His book was in the library of every educated Viennese—as it was on the bookshelf of my home.

Mautner first pointed out that language is not “message.” It is not “medium.” It is meaning as well. In fact, Ludwig Wittgenstein is Mautner’s heir, and, so to speak, Mautner’s testamentary executor—most of what is in Wittgenstein Mautner had groped for forty and fifty years earlier. But then, the Vienna in which I grew up, was also the home of Karl Kraus (1874-1936), arguably the greatest master of the German language in this century.

And for Kraus language was morality. Language was integrity. To corrupt language was to corrupt society and individual alike.

I thus grew up in an atmosphere in which language was taken seriously. And then at nineteen and a trainee in an export firm in Hamburg, I encountered Kierkegaard—then still almost unknown outside his native Denmark, and largely untranslated. The preface to my essay on Kierkegaard in this volume recounts the impact of this experience on me, my work, and my life.

And Kierkegaard preached the sanctity of language. For Kierkegaard, language is aesthetics and aesthetics is morality.

Long before George Orwell I therefore knew that the corruption of language is the tool of the tyrant. It is both a sin and a crime.

For the social ecologist, language is however doubly important. For language is in itself social ecology. For the social ecologist language is not “communication.” It is not just “message.” It is substance. It is the cement that holds humanity together. It creates community and communion.

Thus I always thought that the social ecologist has a responsibility to language. Social ecologists need not be “great” writers; but they have to be respectful writers, caring writers.

The Discipline

I called social ecology a “discipline.” I did not call it a “science.” Indeed I would be quite uncomfortable if anyone spoke of social ecology as a science. It is as different from any of the social sciences as the ecology of the physical universe is different from any of the physical sciences.

“Zum Sehen Geboren; Zum Schauen Bestellt”

(Born to See; Meant to Look)

sings the look-out in Goethe’s Faust. This, I think, is the motto of the social ecologist and of social ecology as a discipline. It is based on looking rather than on analysis. It is based on perception. This, I submit, distinguishes it from what is normally meant by a science. It is not only that it cannot be reductionist. By definition it deals with configurations. They may not be greater than the sums of their parts. But they are fundamentally different.

But also social ecology as a discipline deals with action. Knowledge is a tool to action rather than an end in itself. Social Ecology, as I said before, is a “practice.”

Finally,

social ecology is not “value free.” If it is a science at all, it is a “moral science”

—to use an old term that has been out of fashion for 200 years. The physical ecologist believes, must believe, in the sanctity of natural creation.

The social ecologist believes, must believe, in the sanctity of spiritual creation.

There is a great deal of talk today about “empowering people.” This is a term I have never used and never will use.

Fundamental to the discipline of social ecology, as I see it, is not a belief in power. It is the belief in responsibility, in authority grounded in competence, and in compassion.

Adapted from “The Ecological Vision”, P.441-457