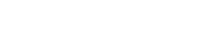

Reflections of a Social Ecologist (Part 1)

Peter F. Drucker

“Born to See, Meant to Look”

The Themes

It was with the tension between continuity and change that my own work began.

I was barely twenty at the time, in early 1930. I was then living in Frankfurt and working as foreign and financial writer for the city’s main afternoon paper. But I also attended law school at the university where I studied international relations and international law, political theory, and the history of legal institutions. The Nazis were not yet in power. Indeed reasonable people were quite sure that they would never get into power—I knew even at that time that they were likely to be wrong. All around me society, economy, and government—indeed civilization—were collapsing. There was a total lack of continuity.

And this drew my attention to that remarkable trio of German thinkers who in a similar period of social collapse, a little over a hundred years earlier, had created stability by inventing what came to be known as Der Rechtsstaat—the best translation of that difficult word may be the Justice State. They were a remarkable trio, both because of the breadth of interests and activities of each of them, but also because they were respectively an agnostic Protestant, a romantic Catholic, and a converted Jew. The first of them, Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835) was the last great figure of the European Enlightenment, a leading statesman during the Napoleonic Wars, the founder of the first modem university, the University of Berlin in 1809, and later the founder of scientific linguistics. The second, Joseph von Radowitz (1797-1853) was a professional soldier and the King’s confidant and first minister, but also a crusading magazine editor and the progenitor of all Catholic parties in Europe—in Germany, in France, in Italy, in Holland, in Belgium, in Austria.

The third and last, Friedrich Julius Stahl (1802-1861), was Hegel’s successor as professor of philosophy at the University of Berlin. A legal philosopher he also revived the moribund theology of Lutheran Protestantism. And he was the most brilliant parliamentarian, in fact the only brilliant parliamentarian in German history.

The three do not enjoy a good press. They are suspect precisely because they tried to balance continuity and change, that is, because they were neither unabashed liberals nor unabashed reactionaries. They tried to create a stable society and a stable polity that would preserve the traditions of the past and yet make possible change, and indeed very rapid change. And they succeeded brilliantly. They created the only political theory that originated on the continent of Europe in modern times—at least until Karl Marx fifty years later. But they also created a political structure that survived for almost a hundred years, until it came crashing down with World War I.

Its failure, the inability to get the military under civilian control—the major cause of the collapse of nineteenth-century Europe—the Rechtsstaat shared with all continental regimes, whether democracies, like the France of the Second Republic (as was demonstrated only too clearly in the Dreyfus Affair of 1896), or the absolute monarchy of the Russian Tsar—or of course with the constitutional monarchy of Meiji Japan as well. During the entire nineteenth century only English-speaking countries succeeded in establishing civilian control of the military and with it civilian control of foreign policy.

Of course, Humboldt, Radowitz, and Stahl did not realize that what they were trying to do had actually been accomplished in the United States. They did not realize that the United States Constitution first and so far practically alone among written constitutions, contains explicit provisions how to be changed. This probably explains more than anything else why, alone of all written constitutions, the American Constitution is still in force and a living document. Even less did they realize the importance of the Supreme Court as the institution which basically represents both conservation and continuity, and innovation and change and balances the two.

But then nobody else in Europe has ever seen this. Tocqueville did not see this. Nor did Bagehot, otherwise a shrewd student of America, nor did Bryce in his monumental work on the American Commonwealth. To this day, by the way, few people in Europe seem to understand this. At least I have never been able to explain to any European the particular role of the Supreme Court—nor by the way was Mr. Justice Holmes able to explain it to his great English friend, Sir Frederick Pollock, as witness their correspondence.

To a European it is simply axiomatic that an independent judiciary and a political role are incompatible and are in fact a contradiction in terms.

And I too, it should be said, had no inkling in 1930 that what the three Germans in the early years of the nineteenth century had tried to accomplish had already been done, and far more successfully, by the Founding Fathers and by Chief Justice Marshall in the infant United States.

What Humboldt did was to balance two conserving institutions: a professional and university-trained civil service and a professional army, with two innovating institutions: the research university with complete freedom of research, publishing, and teaching, and the free-market economy on Adam Smith’s prescription. The Monarch—a strong executive, very similar to the way Humboldt saw George Washington in far away America—would preside above the four and would serve as the balancing wheel. And, to repeat, this worked for a hundred years. While far from a “liberal democracy”—in fact there was not even a parliament in Humboldt’s original formula—it put king, civil service, and, at least in theory, the military under the Law; and at the same time it provided the foundation for the explosive rise to world leadership of the German university and of the Germany economy.

The book on the three and on the Rechtsstaat became the first of many, many books I should have written but did not write, or at least did not finish. The only part of it that was published was a monograph on Stahl—all of thirty-two printed pages. It was written during 1932 as an anti—Nazi manifesto—for Stahl the great conservative had been a Jew. It was meant to make it impossible for the Nazis ever to have any use for me and for me ever to have any use for them. And it was meant also, in the event of a Nazi victory to be among the first books they would banish. It succeeded in its objectives. It was accepted by Germany’s leading social science publisher, Mohr in Tuebingen, and published as Number 100 in the prestigious series on law and government—a singular honor for a totally unknown, twenty-three year old. It came out—a pure coincidence, but still very much to my delight—two weeks after Hitler and seized power in 1933—and it was promptly banned by the Nazis.

What made me abandon the work on the Rechsstaat was, of course, the coming to power of the Nazis in Germany, and with it the failure to maintain any continuity. Out of this came my first major book The End of Economic Man (finished in 1937, published in early 1939). It chronicles the collapse of a society that had lost all continuity and all belief, a society plunged into abject fear and despair. This was then followed by the Future of Industrial Man in 1942 in which I tried to develop social theory and social structure for an industrial society which can both conserve and innovate. This lead directly to my work on the analysis of the institution through which industrial society gives status and function and integrates individual efforts into common achievement, Concept of the Corporation published in 1946.

But over the years I began to realize that change too has to be managed. In fact, I came to realize that

the only way in which an institution, whether a government, a university, a business, a labor union, an army, can maintain continuity is by building systematic, organized, innovation into its very structure.

This finally lead to my 1986 book Innovation and Entrepreneurship which tries to develop a discipline of innovation as a systematic activity.

My concern with the tension between continuity and change as a central polarity in society also led to a growing interest in technology.

But even though I got to serve as president of the Society for the History of Technology, my interest has never been in technology as technology.

I became interested because I found that technology has never been integrated into the study of society.

The technologists look upon technology as having to do with tools. Historians, economists, philosophers—excepting only Karl Marx and Joseph Schumpeter—see technology as a demonic force outside their universe and perpetually threatening it. I see technology as a human activity in society. I see technology in fact as Alfred Russell Wallace, a theorist of evolution and a contemporary of Charles Darwin saw it: “Man” Wallace said,

“is the only animal capable of conscious evolution; he invents tools.”

And it soon became obvious to me that work is a central factor in shaping and molding society, social order, and community. In fact to me it became more and more clear that society is held in tension between two poles, the pole of great ideas, especially of course great religious ideas, and the pole of how man works. To me therefore technology deals with how man works rather than with tools per se.

And so I began to think about a book tentatively entitled “A History of Work.” It too is one of the many books I never wrote. But the products of this interest, a number of short papers on technology’s history and its characteristics, are included in this volume.

Out of the concern with the tension between continuity and change came finally my interest in organizations.

It became clear to me, during the early days of World War II, that we had moved or were moving into a society of organizations in which major social tasks are being performed in and through managed institutions. The first one to attract my attention was the business enterprise—for the simple reason that it was the institution through which the tasks of war-time America were being discharged, the institution which enabled America to win the war.

I have already mentioned my book Concept of the Corporation (1946) which was the first book to attempt the study of a major enterprise—in this case the General Motors Corporation, then the world’ premier manufacturing business and its most successful one—from the inside, as a social organization, and as one that organizes power, authority, responsibility, that is the tasks which always had been seen as tasks of governance if not of government. This book was then followed in 1949 by Landmarks of Tomorrow—and ten years later by The New Society. In The New Society I first talked of a society of organizations but also of knowledge work and knowledge worker as becoming the new social and economic centers. Fifteen years later I then commented on another major change in the society of organization in a 1976 book (reprinted in the Transaction series under the title The Pension Fund Revolution); the original title was The Unseen Revolution.

When I began to study organizations in the 1940s everybody, including myself, saw only two: government, the old one, and business enterprise, the new one. By the late 1940s I myself had already begun to work actively with nonprofit institutions, for example, hospitals. But I did so as something ordinary decency demanded of a citizen. I did it as an act of charity in other words. It slowly dawned on me—I must admit very slowly—that these institutions were of importance in their own right and particularly in America. It gradually dawned on me that this “third sector” is fundamentally distinct from both government and business. Government commands; it tries to obtain compliance. Business supplies; it tries to get paid.

The nonprofit institutions however are human-change agents. Their “product” is neither compliance nor a sale. It is a patient who leaves the hospital cured. It is a student who has learned something. It is a churchgoer whose life is being changed.

In addition, as I learned, gradually these institutions discharge a second and equally important task in American society: they provide effective citizenship. In modem society direct citizenship is no longer possible. All we can do is vote and pay taxes. As volunteers in the nonprofit institutions we are again citizens. We again have an impact on social order, social values, social behavior, social vision. We have social results . It is thus the nonprofit institution which increasingly creates citizenship and community. And in the United States every other adult by 1990 had come to work as a “volunteer” in a nonprofit institution, on average three hours a week. And so increasingly I began to work with the nonprofit sector as a major constituent of society—the end result was my 1990 book Managing the Non-Profit Organization.

But long before that, of course, I had begun to study the management of organizations—at first of the business enterprise and then of organizations altogether—in my various management books, beginning with my 1954 Practice of Management leading to the first book on what is now called strategy: Managing for Results (1964), then the Effective Executive (1966), an attempt to project what had been known from Plato to Machiavelli as “the education of the ruler” into “the education of the executive in the organization.” In 1973 I then put together twenty years of management work in a big book Management, Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices.

The focus of my early work, the work from the 1930s until the early 1960s, was on the new social phenomenon, the organization, its structure, its constitution, its management, its functions. But I knew myself from the early days to be out of sympathy with the basic trend of my times, the trend towards centralization, towards monolithic society and towards government omnipotence.

This trend had its origin in World War I which was as much a triumph of the civilian bureaucracy as it was an abject failure of military leadership. The Western world came out of World War I convinced of its ability to predict the future and to make it through planning. It came out of it with the belief that there was no limit to government’s ability to tax and therefore to government’s ability to spend—of all the lessons of World War I this was probably the most deleterious one. And it came out with the conviction that government could do and in fact should do everything.

Everybody believes that democracies and totalitarian regimes had nothing in common in the seventy years between 1920 and the collapse of communism. This is half-truth only. Both shared the belief in centralization and government, a belief that probably reached its peak during the Kennedy years in the United States.

Indeed the belief was so prevalent that Stalinism, that most traditional of oriental despotisms, could wrap itself in the cloak of being “progressive” and indeed “revolutionary” by waving the banner of planning, of state control, of total centralization.

Of course, there was always opposition. But the opposition did not as a rule question the competence and ability of government to do everything and to be everything. It questioned the wisdom of doing so. When Friedrich von Hayek (1899-1991) in 1944 published The Road to Serfdom—and thereby started what we now call neoconservatism—he pointed out that socialist government must be a tyranny. But he did not question its ability to perform politically or economically (he did this only more than forty years later in his 1988 book The Fatal Conceit by which time the total incompetence, political, social, moral, economic, of socialist regimes had become clear to everybody).

In other words for five decades we asked what should government do? Very few people, if any, asked what can government do.

To me this question became, however, a central question fairly early. I probably owe this also to my interest in those German liberal conservatives (or conservative liberals), Humboldt, Radowitz, and Stahl. For Humboldt, while a very young man, barely twenty-five, and living as a student in the Paris of the French Revolution, had written a little book called The Limits of the Effectiveness of Government (Die Grenzen der Wirksamkeit des Staates)—which however was not published during his lifetime, being much too unfashionable even then.

I began to ask the same question: what are the limits of government’s effectiveness? in the early years after World War II and began to ask it with increasing urgency as we went into the Eisenhower administration. I first raised it obliquely in my 1959 book Landmarks of Tomorrow and then head-on, in my 1969 book The Age of Discontinuity. It is a central theme of my 1989 book The New Realities and is being discussed in considerable depths in a chapter entitled “the Megastate and Its Failure” in a book I am presently (1992) working on, tentatively entitled The Post-Capitalist Society.

And thus my work began to embrace both the political and the social institutions of modem society.

By the late 1950s another major theme had begun to appear in my work:

the emergence of knowledge as central resource, and of the knowledge society (a word I coined in the late 1950s).

The characteristics of knowledge—and it is totally different from any other resource in society and economy—the responsibilities of knowledge; the place and function of the knowledge worker; and the productivity of knowledge work, are themes discussed in my writing, and in a good many of the articles in this volume.

Finally there is one continuing theme, from my earliest to my latest book: the freedom, the dignity, the status of the person in modem society, the role and function of organization as instrument of human achievement, human growth and human fulfillment, and the need of the individual for both, society and community.

Adapted from “The Ecological Vision”, P.441-457