Primum Non Nocere: The Ethics of Responsibility

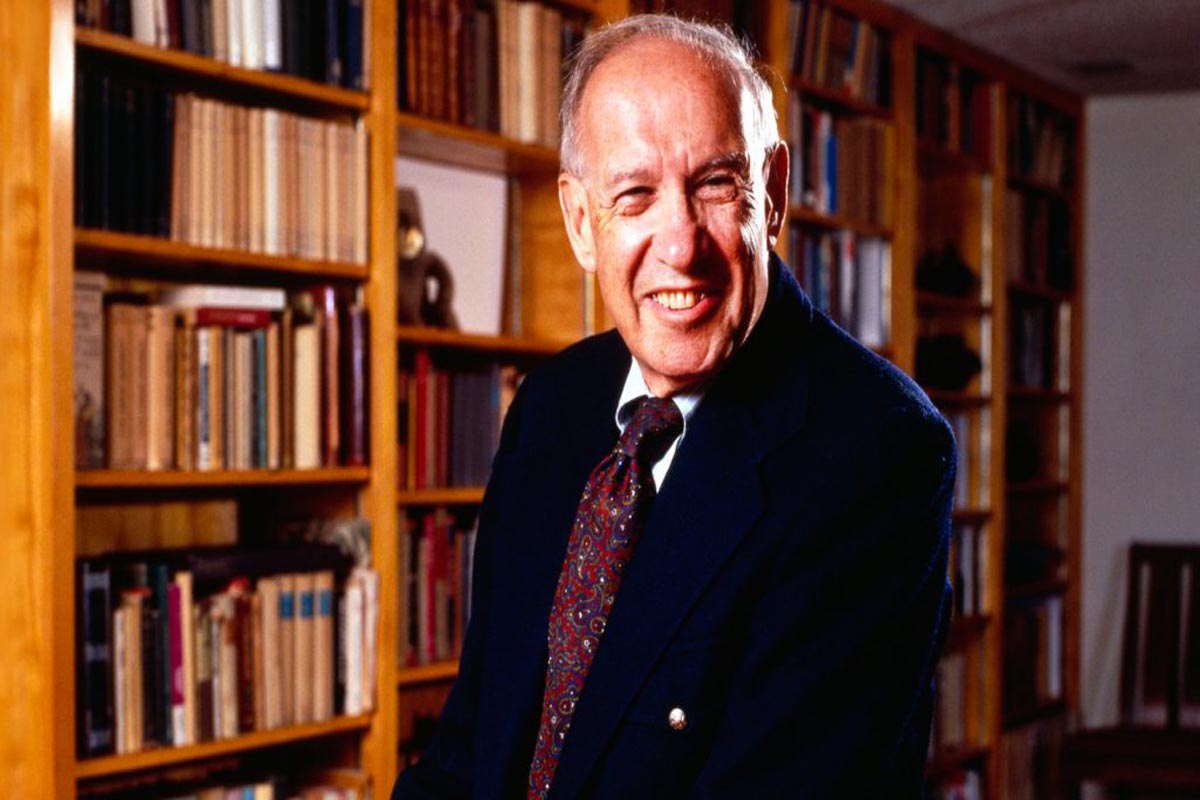

PETER F. DRUCKER

"Primum non nocere, 'not knowingly to do harm,' is the basic rule of professional ethics, the basic rule of an ethics of public responsibility"

Countless sermons have been preached and printed on the ethics of business or the ethics of the businessman. Most have nothing to do with business and little to do with ethics.

One main topic is plain, everyday, honesty. Businessmen, we are told solemnly, should not cheat, steal, lie, bribe, or take bribes. But nor should anyone else.

Men and women do not acquire exemption from ordinary rules of personal behavior because of their work or job. Nor, however, do they cease to be human beings when appointed vice-president, city manager, or college dean. And there has always been a number of people who cheat, steal, lie, bribe, or take bribes. The problem is one of moral values and moral education, of the individual, of the family, of the school. But there neither is a separate ethics of business, nor is one needed.

All that is needed is to mete out stiff punishments to those—whether business executives or others—who yield to temptation. In England a magistrate still tends to hand down a harsher punishment in a drunken-driving case if the accused has gone to one of the well-known public schools or to Oxford or Cambridge. And the conviction still .rates a head-line in the evening paper: “Eton graduate convicted of drunken driving.” No one expects an Eton education to produce temperance leaders. But it is still a badge of distinction, if not of privilege. And not to treat a wearer of such a badge more harshly than an ordinary workingman who has had one too many would offend the community’s sense of justice. But no one considers this a problem of the “ethics of the Eton graduate.” The other com-mon theme in the discussion of ethics in business has nothing to do with ethics.

Such things as the employment of call girls to entertain customers are not matters of ethics but matters of esthetics. “Do I want to see a pimp when I look at myself in the mirror while shaving?” is the real question.

It would indeed be nice to have fastidious leaders. Alas, fastidiousness has never been prevalent among leadership groups, whether kings and counts, priests or generals, or even “intellectuals” such as the painters and humanists of the Renaissance, or the “literati” of the Chinese tradition. All a fastidious man can do is withdraw personally from activities that violate his self-respect and his sense of taste.

Lately these old sermon topics have been joined, especially in the U.S., by a third one: managers, we are being told, have an “ethical responsibility” to take an active and constructive role in their community, to serve community causes, give of their time to com-munity activities, and so on. There are many countries where such community activity does not fit the traditional mores; Japan and France would be examples. But where the community has a tradition of “voluntarism”—that is, especially in the U.S.—managers should indeed be encouraged to participate and to take responsible leadership in community affairs and community organizations. Such activities should, however, never be forced on them nor should they be appraised, rewarded, or promoted according to their participation in voluntary activities. Ordering or pressuring managers into such work is abuse of organizational power and illegitimate.

An exception might be made for managers in businesses where the community activities are really part of their obligation to the business. The local manager of the telephone company, for instance, who takes part in community activities, does so as part of his managerial duties and as the local public-relations representative of his company. The same is true of the manager of a local Sears, Roebuck store. And the local real estate man who belongs to a dozen different community activities and eats lunch every day with a different “service club” knows perfectly well that he is not serving the community but promoting his business and hunting for prospective customers.

But, while desirable, community participation of managers has nothing to do with eth-ics, and not much to do with responsibility. It is the contribution of an individual in his capacity as a neighbor and citizen. And it is something that lies outside his job and out-side his managerial responsibility.

Leadership Groups but Not Leaders

A problem of ethics that is peculiar to the manager arises from the fact that the managers of institutions are collectively the leadership groups of the society of organizations. But individually a manager is just another fellow employee.

This is clearly recognized by the public. Even the most powerful head of the largest corporation is unknown to the public. Indeed most of the company’s employees barely know his name and would not recognize his face. He may owe his position entirely to personal merit and proven performance. But he owes his authority and standing entirely to his institution. Everybody knows GE, the Telephone Company, Mitsubishi, Siemens, and Unilever. But who heads these great corporations—or for that matter, the University of California, the École Polytechnique or Guy’s Hospital in London—is of direct interest and concern primarily to the management group within these institutions.

It is therefore inappropriate to speak of managers as leaders. They are “members of the leadership group.” The group, however, does occupy a position of visibility, of prominence, and of authority. It therefore has responsibility—and it is with this responsibility that the preceding chapters of this section are concerned.

But what are the responsibilities, what are the ethics of the individual manager, as a member of the leadership group?

Essentially being a member of a leadership group is what traditionally has been meant by the term “professional.” Membership in such a group confers status, position, prominence, and authority. It also confers duties. To expect every manager to be a leader is futile. There are, in a developed society, thousands, if not millions, of managers—and leadership is always the rare exception and confined to a very few individuals. But as a member of a leadership group a manager stands under the demands of professional ethics—the demands of an ethic of responsibility.

Adapted from “Management: Tasks,Responsibilities,Practices”, P.254-260